- Modern Indian History Tutorial

- Modern Indian History - Home

- Decline of Mughal Empire

- Bahadur Shah I

- Jahandar Shah

- Farrukh Siyar

- Muhammad Shah

- Nadir Shah’s Outbreak

- Ahmed Shah Abdali

- Causes of Decline of Mughal Empire

- South Indian States in 18th Century

- North Indian States in 18th Century

- Maratha Power

- Economic Conditions in 18th Century

- Social Conditions in 18th Century

- Status of Women

- Arts and Paintings

- Social Life

- The Beginnings of European Trade

- The Portuguese

- The Dutch

- The English

- East India Company (1600-1744)

- Internal Organization of Company

- Anglo-French Struggle in South India

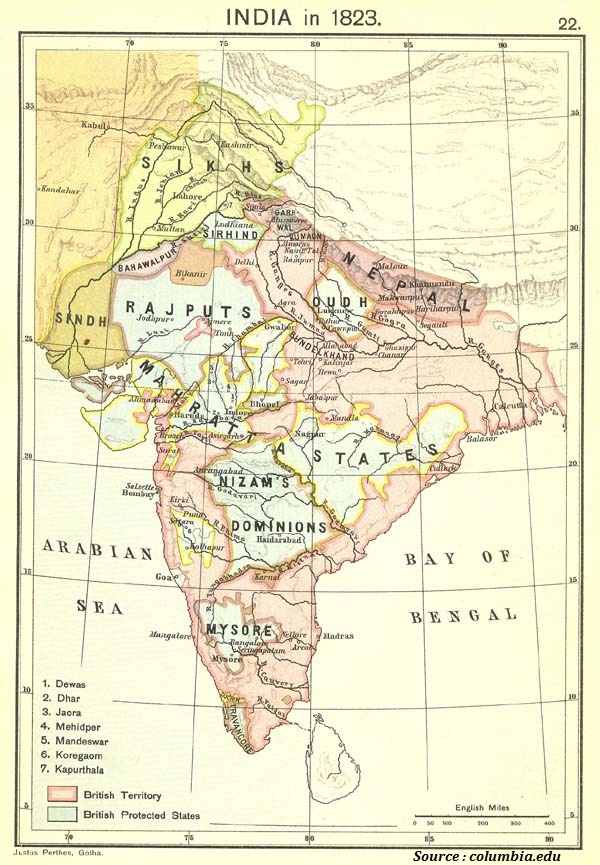

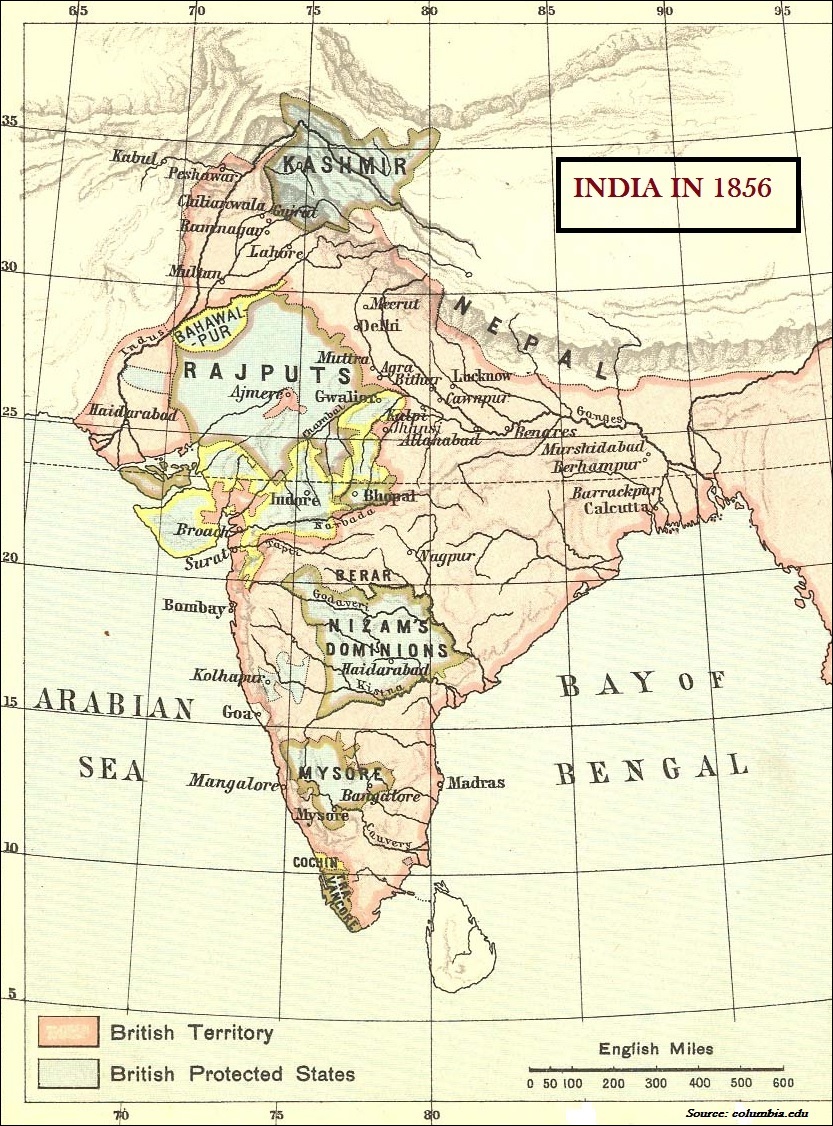

- The British Conquest of India

- Mysore Conquest

- Lord Wellesley (1798-1805)

- Lord Hastings

- Consolidation of British Power

- Lord Dalhousie (1848-1856)

- British Administrative Policy

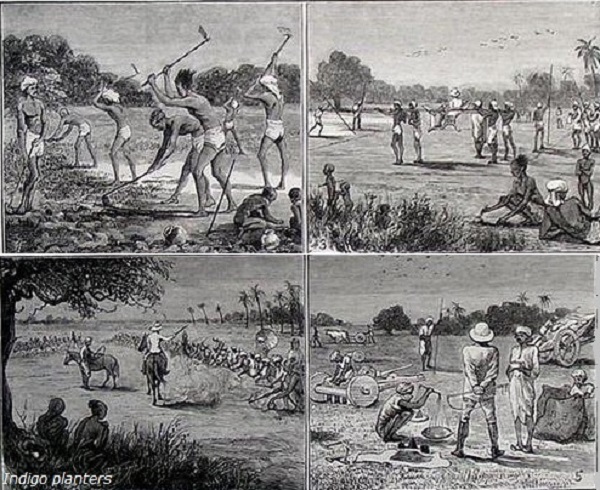

- British Economic Policies

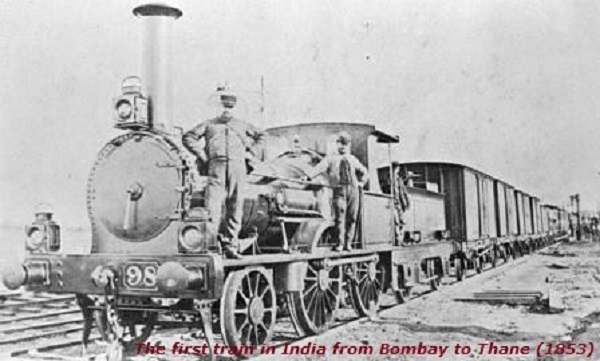

- Transport and Communication

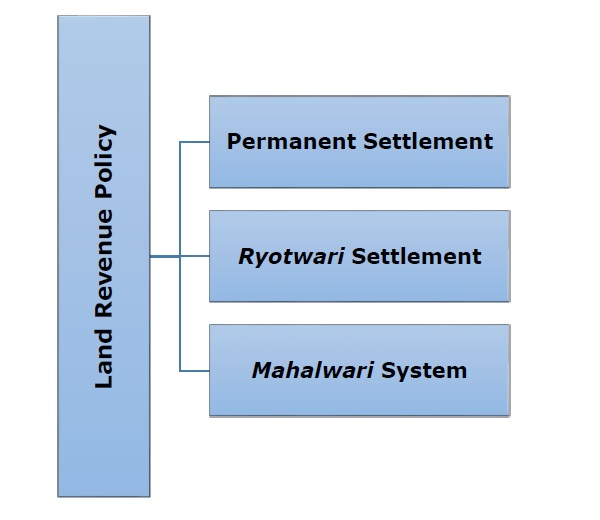

- Land Revenue Policy

- Administrative Structure

- Judicial Organization

- Social and cultural Policy

- Social and Cultural Awakening

- The Revolt of 1857

- Major Causes of 1857 Revolt

- Diffusion of 1857 Revolt

- Centers of 1857 Revolt

- Outcome of 1857 Revolt

- Criticism of 1857 Revolt

- Administrative Changes After 1858

- Provincial Administration

- Local Bodies

- Change in Army

- Public Service

- Relations with Princely States

- Administrative Policies

- Extreme Backward Social Services

- India & Her Neighbors

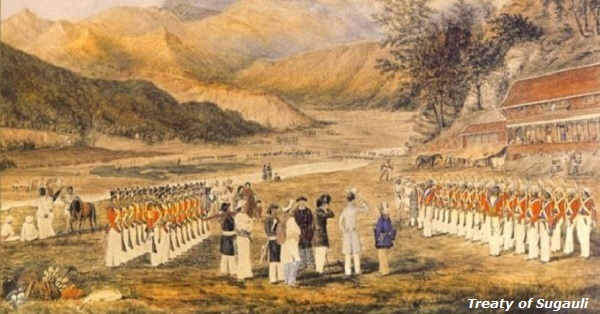

- Relation with Nepal

- Relation with Burma

- Relation with Afghanistan

- Relation with Tibet

- Relation with Sikkim

- Relation with Bhutan

- Economic Impact of British Rule

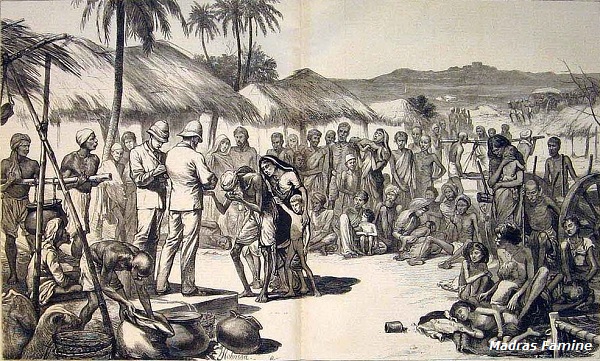

- Nationalist Movement (1858-1905)

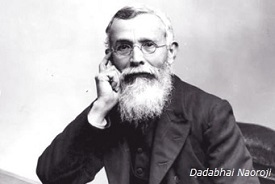

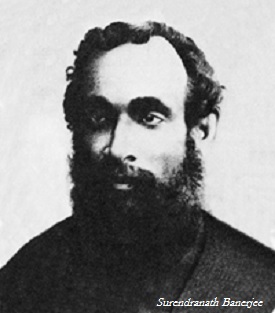

- Predecessors of INC

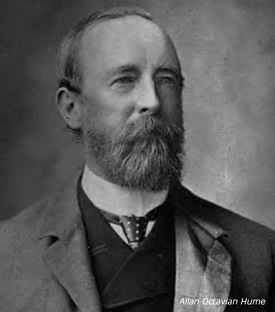

- Indian National Congress

- INC & Reforms

- Religious & Social Reforms

- Religious Reformers

- Women’s Emancipation

- Struggle Against Caste

- Nationalist Movement (1905-1918)

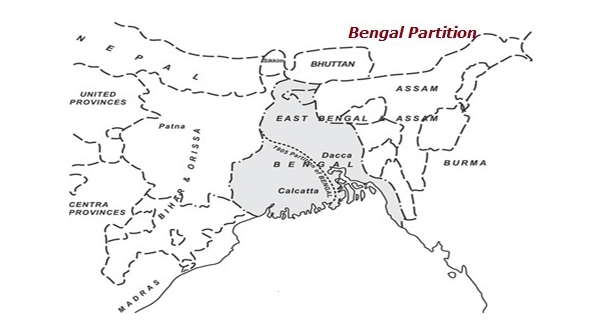

- Partition of Bengal

- Indian National Congress (1905-1914)

- Muslim & Growth Communalism

- Home Rule Leagues

- Struggle for Swaraj

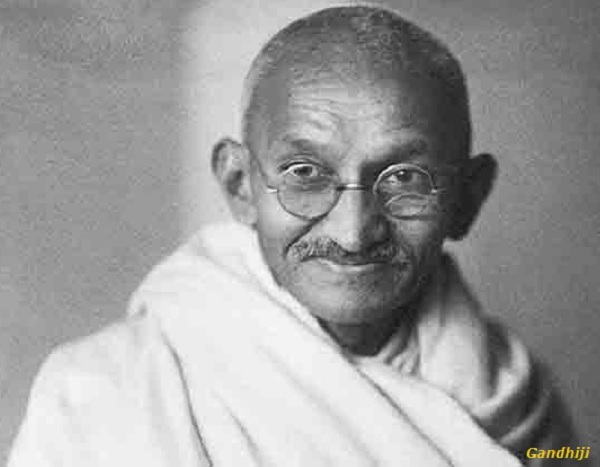

- Gandhi Assumes Leadership

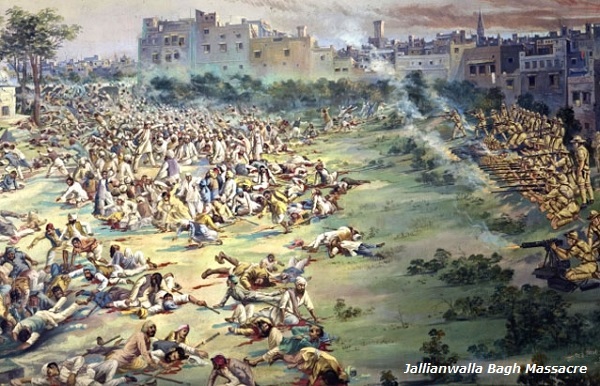

- Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre

- Khilafat & Non-Cooperation

- Second Non-Cooperation Movement

- Civil Disobedience Movement II

- Government of India Act (1935)

- Growth of Socialist Ideas

- National Movement World War II

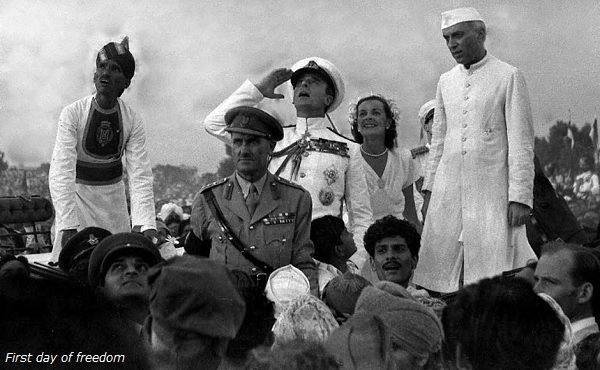

- Post-War Struggle

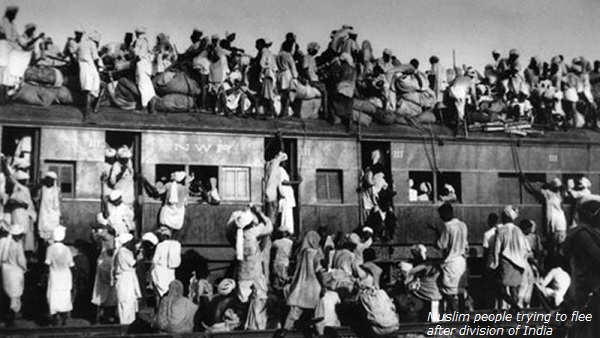

- Clement Attlee’s Declaration

- Reference & Disclaimer

Modern Indian History - Quick Guide

Decline of Mughal Empire

The Great Mughal Empire declined and disintegrated during the first half of the 18th century.

The Mughal Emperors lost their power and glory and their empire shrank to a few square miles around Delhi.

In the end, in 1803, Delhi itself was occupied by the British army and the proud of Mughal Emperor was reduced to the status of a mere pensioner of a foreign power.

The decline of Mughal Empire reveals some of the defects and weaknesses of India's medieval social, economic, and political structure which were responsible for the eventual subjugation of the country by the English East India Company.

The unity and stability of the Empire had been shaken up during the long and strong reign of Aurangzeb; yet in spite of his many harmful policies, the Mughal administration was still quite efficient and the Mughal army quite strong at the time of his death in 1707.

For better understanding (of the decline of Mughal Empire), the subsequent chapters (kept under the following headings) describe feeble Mughal Emperors, their weaknesses, and faulty activities −

- Bahadur Shah I

- Jahandar Shah

- Farrukh Siyar

- Muhammad Shah

- Nadir Shah’s Outbreak

- Ahmad Shah Abdali

Modern Indian History - Bahadur Shah I

On Aurangzeb's death, his three sons fought among themselves for the throne. The 65-year old Bahadur Shah emerged victorious. He was learned, dignified, and deserving.

Bahadur Shah followed a policy of compromise and conciliation, and there was evidence of the reversal of some of the narrow-minded policies and measures adopted by Aurangzeb. He adopted a more tolerant attitude towards the Hindu chiefs and rajas.

There was no destruction of temples in Bahadur Shah’s reign. In the beginning, he made an attempt to gain greater control over the regional states through the conciliation; however, dissensions developed among the regional kingdoms (including Rajput, Marathas, etc.); resultantly, they fought among themselves as well as against Mughal Emperor.

Bahadur Shah had tried to conciliate the rebellious Sikhs by making peace with Guru Gobind Singh and giving him a high mansab (rank). But after the death of the Guru, the Sikhs once again raised the banner of revolt in Punjab under the leadership of Banda Bahadur. The Emperor decided to take strong measures and himself led a campaign against the rebels, soon controlled practically the entire territory between the Sutlej and the Yamuna, and reached the close neighborhood of Delhi.

Bahadur Shah conciliated Chatarsal (the Bundela chief, who remained a loyal feudatory) and the Jat chief Churaman, who joined him in the campaign against Banda Bahadur.

In spite of hard efforts of Bahadur Shah, there was further deterioration in the field of administration in Bahadur Shah's reign. The position of state finances worsened as a result of his reckless grants and promotions.

During Bahadur Shah's reign, the remnants of the Royal treasure, amounting to some total 13 crores of rupees in 1707, were exhausted.

Bahadur Shah was examining towards a solution of the problems besetting the Empire. He might have revived the Imperial fortunes, but unfortunately, his death in 1712 plunged the Empire once again into civil war.

Modern Indian History - Jahandar Shah

After Bahadur Shah’s death, a new element entered Mughal politics i.e. the succeeding wars of succession. While previously the contest for the power had been between royal princes only, and the nobles had hardly any interference to the throne; now ambitious nobles became direct contenders for the power and used princes as mere pawns to capture the seats of authority.

In the civil war, one of Bahadur Shah's weak sons, Jahandar Shah, won because he was supported by Zulfiqar Khan, the most powerful noble of the time.

Jahandar Shah was a weak and degenerate prince who was wholly devoted to pleasure. He lacked good manners, dignity, and decency.

During Jahandar Shah's reign, the administration was virtually in the hands of the extremely capable and energetic Zulfiqar Khan, who was his wazir.

Zulfiqar Khan believed that it was necessary to establish friendly relations with the Rajput rajas and the Maratha Sardars and to conciliate the Hindu chieftains necessary to strengthen his own position at the Court and to save the Empire. Therefore, he swiftly reversed the policies of Aurangzeb and abolished the hated jzyah (tax).

Jai Singh of Amber was given the title of Mira Raja Saint and appointed Governor of Malwa; Ajit Singh of Marwar was awarded the tide of Maharaja and appointed Governor of Gujarat.

Zulfiqar Khan made an attempt to secure the finances of the Empire by checking the reckless growth of jagirs and offices. He also tried to compel the (nobles) to maintain their official quota of troops.

An evil tendency encouraged by him was that of ‘ijara’ or revenue-farming. Instead of collecting land revenue at a fixed rate as under Todar Mal’s land revenue settlement, the Government began to contract with revenue farmers and middlemen to pay the Government a fixed amount of money while they were left free to collect whatever they could from the peasant. This encouraged the oppression of the peasant.

Many jealous nobles secretly worked against Zulfiqar Khan. Worse still, the Emperor did not give him his trust and cooperation in full measure. The Emperor's ears were poisoned against Zulfiqar Khan by unscrupulous favorites. He was told that his wazir was becoming too powerful and ambitious and might even overthrow the Emperor himself.

The cowardly Emperor could not dismiss the powerful wajir (Zulfiqar Khan), but he began to intrigue against him secretly.

Modern Indian History - Farrukh Siyar

Jahandar Shah's inglorious reign came to an early end in January 1713 when he was defeated at Agra by his nephew Farrukh Siyar.

Farrukh Siyar owed his victory to the Sayyid brothers, Abdullah Khan and Husain Ali Khan Baraha, who were therefore given the offices of wazir and nur bakshi respectively

The Sayyid brothers soon acquired dominant control over the affairs of the state and Farrukh Siyar lacked the capacity to rule. He was coward, cruel, undependable, and faithless. Moreover, he allowed himself to be influenced by worthless favorites and flatterers.

In spite of his weaknesses, Farrukh Siyar was not willing to give the Sayyid brothers a free hand but wanted to exercise personal authority.

The Sayyid brothers were convinced that administration could be carried on properly, the decay of the Empire checked, and their own position safeguarded only if they wielded real authority and the Emperor merely reigned without ruling.

There was a prolonged struggle for power between the Emperor Farrukh Siyar and his wazir and mir bakshi.

Year after year the ungrateful Emperor intrigued to overthrow the two brothers, but he failed repeatedly. In the end of 1719, the Sayyid brothers deposed Farrukh Siyar and killed him.

In Farrukh Siyar place, they raised to the throne in quick succession two young princes' namely Rafi-ul Darjat and Rafi ud-Daulah (cousins of Farrukh Siyar), but they died soon. The Sayyid brothers now made Muhammad Shah the Emperor of India.

The three successors of Farrukh Siyar were mere puppets in the hands of the Saiyids Even their personal liberty to meet people and to move around was restricted. Thus, from 1713 until 1720, when they were overthrown, the Sayyid brothers wielded the administrative power of the state.

The Sayyid brothers made a rigorous effort to control rebellions and to save the Empire from administrative disintegration. They failed in these tasks mainly because they were faced with constant political rivalry, quarrels, and conspiracies at the court.

The everlasting friction in the ruling circles disorganized and even paralyzed administration at all levels and spread lawlessness and disorder everywhere.

The financial position of the state deteriorated rapidly as zamindars and rebellious elements refused to pay land revenue, officials misappropriated state revenues, and central income declined because of the spread of revenue farming.

The salaries of officials and soldiers could not be paid regularly and soldiers became undisciplined and even mutinous.

Many nobles were jealous of the 'growing power’ of the Sayyid brothers. The deposition and murder of Farrukh Siyar frightened many of them: if the Emperor could be killed, what safety was there for mere nobles?

Moreover, the murder of the Emperor created a wave of public revulsion against the two brothers. They were looked down upon as traitors.

Many of the nobles of Aurangzeb's reign also disliked the Sayyid alliance with the Rajput and the Maratha chiefs and their liberal policy towards the Hindus.

Many nobles declared that the Sayyids were following anti-Mughal and antiIslamic policies. They thus tried to arouse the fanatical sections of the Muslim nobility against the Sayyid brothers.

The anti- Sayyid nobles were supported by Emperor Muhammad Shah who wanted to free himself from the control of the two brothers.

In 1720, Haidar Khan killed Hussain Ali khan on 9 October 1720, the younger of the two brothers. Abdullah Khan tried to fight, back but was defeated near Agra. Thus ended the domination of the Mughal Empire by the Sayyid brothers (they were known in Indian history as 'king makers').

Modern Indian History - Muhammad Shah

Muhammad Shah's long reign of nearly 30 years (1719-1748) was the last chance of saving the Empire. But Muhammad Shah was not the man of the moment. He was weak-minded and frivolous and over-fond of a life of ease and luxury.

Muhammad Shah neglected the affairs of state. Instead of giving full support to knowledgeable wazirs such as Nizam-ul-Mulk, he fell under the evil influence of corrupt and worthless flatterers and intrigued against his own ministers. He even shared in the bribes taken by his favorite courtiers.

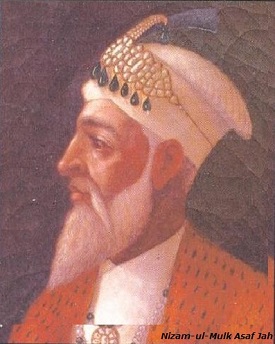

Disgusted with the fickle-mindedness and suspicious nature of the Emperor and the constant quarrels at the court, Nizum-ul-Mulk, the most powerful noble of the time, decided to follow his own ambition. He had become the wazir in 1722 and had made a vigorous attempt to reform the administration.

Nizum-ul-Mulk decided to leave the Emperor and his Empire to their fate and to strike out on his own. He relinquished his office in October 1724 and marched south to find the state of Hyderabad in the Deccan. "His departure was symbolic of the flight of loyalty and virtue from the Empire.”

After the withdrawal of Nizum-ul-Mulk, many other zamindars, rajas, and nawabs of many states raised the banner of rebellion and independence. For example Bengal, Hyderabad, Avadh, Punjab, and Maratha.

Nadir Shah’s Outbreak

In 1738-39, Nadir Shah descended upon the plains of northern India.

Nadir Shah was attracted to India by the fabulous wealth for which it was always famous. The visible weakness of the Mughal Empire made such spoliation possible.

Nadir Shah marched on to Delhi and the Emperor Muhammad Shah was taken as prisoner.

A terrible massacre of the citizens of the imperial capital was ordered by Nadir Shah as a reprisal against the killing of some of his soldiers.

The greedy invader Nadir Shah took possession of the royal treasury and other royal property, levied tribute on the leading nobles, and plundered Delhi.

Nadir Shah’s total plunder has been estimated about 70 crores of rupees. This enabled him to exempt taxation of his own Kingdom for three years.

Nadir Shah also carried away the famous Koh-i-nur diamond and the Jewelstudded Peacock Throne of Shahjahan.

Nadir Shah compelled Muhammad Shah to cede to him all the provinces of the Empire falling west of the river Indus.

Nadir Shah's Invasion inflicted immense damage on the Mughal Empire. It caused an irreparable loss of prestige and exposed the hidden weaknesses of the Empire to the Maratha Sardars and the foreign trading companies.

The invasion ruined imperial finances and adversely affected the economic life of the country. The impoverished nobles began to rack-rent and oppress the peasantry even more in an effort to recover their lost fortunes

The loss of Kabul and the areas to the west of the Indus once again opened the Empire to the threat of invasions from the North-West. A vital line of defense had disappeared.

Modern Indian History - Ahmed Shah Abdali

After Muhammad Shah's death in 1748, bitter struggles, and even civil war broke out among unscrupulous and power hungry nobles. Furthermore, as a result of the weakening of the north-western defenses, the Empire was devastated by the repeated invasions of Ahmed Shah Abdali, one of Nadir Shah's ablest generals, who had succeeded in establishing his authority over Afghanistan after his master's death.

Abdali repeatedly invaded and plundered northern India right down to Delhi and Mathura between 1748 and 1767.

In 1761, Abdali defeated the Maratha in the Third Battle of Panipat and thus gave a big blow to their ambition of controlling the Mughal Emperor and thereby dominating the country.

After defeating Mughal and Maratha, Abdali did not, however, found a new Afghan kingdom in India. He and his successors could not even retain the Punjab which they soon lost to the Sikh chiefs.

As a result of the invasions of Nadir Shah Abdali and the suicidal internal feuds of the Mughal nobility, the Mughal Empire had (by 1761) ceased to exist in practice as an all-India Empire.

Mughal Empire narrowed merely as the Kingdom of Delhi. Delhi itself was a scene of 'daily riot and tumult'.

Shah Alam II, who ascended the throne in 1759, spent the initial years as an Emperor wandering from place to place far away from his capital, for he lived in mortal fear of his own war.

Shah Alam II was a man of some ability and ample courage. But the Empire was by now beyond redemption.

In 1764, Shah Alam II joined Mir Qasim of Bengal and Shuja-ud-Daula of Avadh in declaring war upon the English East India Company.

Defeated by the British at the Battle of Buxar (October 1764), Shah Alam II lived for several years at Allahabad as a pensioner of the East India Company.

Shah Alam II left the British shelter in 1772 and returned to Delhi under the protective arm of the Marathas.

The British occupied Delhi in 1803 and since that time to till 1857, when the Mughal dynasty was finally extinguished, the Mughal Emperors merely served as a political front for the English.

Causes of Decline of Mughal Empire

Beginning of the decline of the Mughal Empire can be traced to the strong rule of Aurangzeb.

Aurangzeb inherited a large empire, yet he adopted a policy of extending it further to the farthest geographical limits in the south at the great expense of men and materials.

Political Cause

In reality, the existing means of communication and the economic and political structure of the country made it difficult to establish a stable centralized administration over all parts of the country.

Aurangzeb’s objective of unifying the entire country under one central political authority was, though justifiable in theory, not easy in practice.

Aurangzeb’s futile but arduous campaign against the Marathas extended over many years; it drained the resources of his Empire and ruined the trade and industry of the Deccan.

Aurangzeb’s absence from the north for over 25 years and his failure to subdue the Marathas led to deterioration in administration; this undermined the prestige of the Empire and its army.

In the 18th century, Maratha’s expansion in the north weakened central authority still further.

Alliance with the Rajput rajas with the consequent military support was one of the main pillars of Mughal strength in the past, but Aurangzeb's conflict with some of the Rajput states also had serious consequences.

Aurangzeb himself had in the beginning adhered to the Rajput alliance by raising Jaswant Singh of Kamer and Jai Singh of Amber to the highest of ranks. But his short-sighted attempt later to reduce the strength of the Rajput rajas and extend the imperial sway over their lands led to the withdrawal of their loyalty from the Mughal throne.

The strength of Aurangzeb’s administration was challenged at its very nerve center around Delhi by Satnam, the Jat, and the Sikh uprisings. All of them were to a considerable extent the result of the oppression of the Mughal revenue officials over the peasantry.

They showed that the peasantry was deeply dissatisfied with feudal oppression by Zamindars, nobles, and the state.

Religious Cause

Aurangzeb's religious orthodoxy and his policy towards the Hindu rulers seriously damaged the stability of the Mughal Empire.

The Mughal state in the days of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shahjahan was basically a secular state. Its stability was essentially founded on the policy of noninterference with the religious beliefs and customs of the people, fostering of friendly relations between Hindus and Muslims.

Aurangzeb made an attempt to reverse the secular policy by imposing the jizyah (tax imposed on non-Muslim people), destroying many of the Hindu temples in the north, and putting certain restrictions on the Hindus.

The jizyah was abolished within a few years of Aurangzeb’s death. Amicable relations with the Rajput and other Hindu nobles and chiefs were soon restored.

Both the Hindu and the Muslim nobles, zamindars, and chiefs ruthlessly oppressed and exploited the common people irrespective of their religion.

Wars of Succession and Civil Wars

Aurangzeb left the Empire with many problems unsolved, the situation was further worsened by the ruinous wars of succession, which followed his death.

In the absence of any fixed rule of succession, the Mughal dynasty was always plagued after the death of a king by a civil war between the princes.

The wars of succession became extremely fierce and destructive during the 18th century and resulted in great loss of life and property. Thousands of trained soldiers and hundreds of capable military commanders and efficient and tried officials were killed. Moreover, these civil wars loosened the administrative fabric of the Empire.

Aurangzeb was neither weak nor degenerate. He possessed great ability and capacity for work. He was free of vices common among kings and lived a simple and austere life.

Aurangzeb undermined the great empire of his forefathers not because he lacked character or ability but because he lacked political, social, and economic insight. It was not his personality, but his policies that were out of joint.

The weakness of the king could have been successfully overcome and covered up by an alert, efficient, and loyal nobility. But the character of the nobility had also deteriorated. Many nobles lived extravagantly and beyond their means. Many of them became ease-loving and fond of excessive luxury.

Many of the emperors neglected even the art of fighting.

Earlier, many able persons from the lower classes had been able to rise to the ranks of nobility, thus infusing fresh blood into it. Later, the existing families of nobles began to monopolies all offices, barring the way to fresh comers.

Not all the nobles, however, bad become weak and inefficient. A large number of energetic and able officials and brave and brilliant military commanders came into prominence during the 18th century, but most of them did not benefit the Empire because they used their talents to promote their own interests and to fight each other rather than to serve the state and society.

The major weakness of the Mughal nobility during the 18th century lay, not in the decline in the average ability of the nobles or their moral decay, but in their selfishness and lack of devotion to the state and this, in turn, gave birth to corruption in administration and mutual bickering.

In order to increase emperors’ power, prestige, and income, the nobles formed groups and factions against each other and even against the king. In their struggle for power, they took recourse to force, fraud, and treachery.

The mutual quarrels exhausted the Empire, affected its cohesion, led to its dismemberment, and, in the end, made it an easy prey to foreign conquerors.

A basic cause of the downfall of the Mughal Empire was that it could no longer satisfy the minimum needs of its population.

The condition of the Indian peasant gradually worsened during the 17th and 18th centuries. Nobles made heavy demands on the peasants and cruelly oppressed them, often in violation of official regulations.

Many ruined peasants formed roving bands of robbers and adventurers, often under the leadership of the zamindars, and thus undermined law and order and the efficiency of the Mughal administration.

During the 18th century, the Mughal army lacked discipline and fighting morale. Lack of finance made it difficult to maintain a large number of army. Its soldiers and officers were not paid for many months, and, since they were mere mercenaries, they were constantly disaffected and often verged on a mutiny.

The civil wars resulted in the death of many brilliant commanders and brave and experienced solders. Thus, the army, the ultimate sanction of an empire, and the pride of the Great Mughals, was so weakened that it could no longer curb the ambitious chiefs and nobles or defend the Empire from foreign aggression.

Foreign Invasion

A series of foreign invasions affected Mughal Empire very badly. Attacks by Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali, which were themselves the consequences of the weakness of the Empire, drained the Empire of its wealth, ruined its trade and industry in the North, and almost destroyed its military power.

The emergence of the British challenge took away the last hope of the revival of the crisis-ridden Empire.

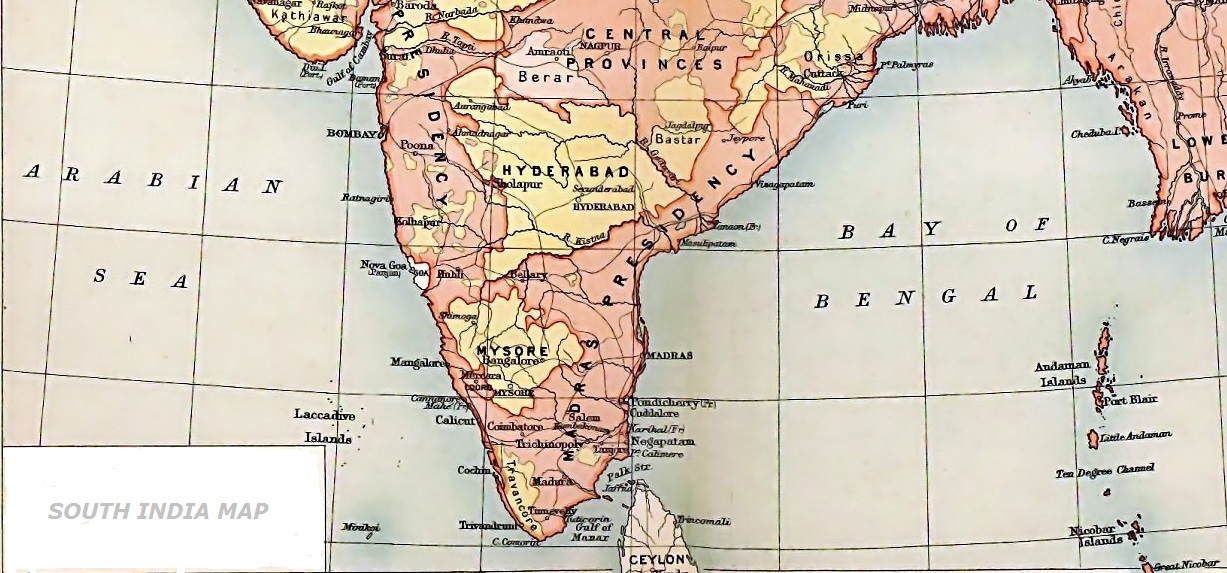

South Indian States in 18th Century

The rulers of the South Indian states established law and order and viable economic and administrative states. They curbed with varying degrees of success.

The politics of South Indian states were invariably non-communal or secular. The motivations of their rulers were being similar in economic and political terms.

The rulers of South Indian states did not discriminate on religious grounds in public appointment; civil or military; nor did the rebels against their authority pay much attention to the religion of the rulers.

None of the South Indian states, however, succeeded in arresting the economic crisis. The zamindars and jagirdars, whose had number constantly increased, continued to fight over a declining income from agriculture, while the condition of the peasantry continued to deteriorate.

While the South Indian states prevented any breakdown of internal trade and even tried to promote foreign trade, they did nothing to modernize the basic industrial and commercial structure of their states.

Following were the important states of South India in 18th century −

Hyderabad and the Carnatic

The state of Hyderabad was founded by Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah in 1724. He was one of the leading nobles of the post-Aurangzeb era.

Asaf Jah never openly declared his independence in front of the Central Government, but in practice, he acted like an independent ruler. He waged wars, concluded peace, conferred titles, and gave jaws and offices without reference to Delhi.

Asaf Jah followed a tolerant policy towards the Hindus. For example, a Hindu, Purim Chand, was his Dewan. He consolidated his power by establishing an orderly administration in Deccan.

After the death of Asaf Jah (in 1748), Hyderabad fell prey to the same disruptive forces as were operating at Delhi.

The Carnatic was one of the subahs of the Mughal Deccan and as such came under the Nizam of Hyderabad's authority. But just as in practice the Nizam had become independent of Delhi, so also the Deputy Governor of the Carnatic, known as the Nawab of Carnatic, had freed himself from the control of the Viceroy of Deccan and made his office hereditary.

Mysore

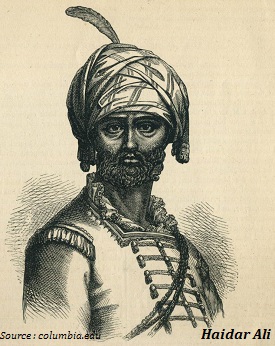

Next to Hyderabad, the most important power that emerged in South India was Mysore under Haidar Ali. The kingdom of Mysore had prescribed its precarious independence ever since the end of the Vijayanagar Empire.

Haidar Ali born in 1721, in an obscure family, started his career as a petty officer in the Mysore army. Though uneducated, he possessed a keen intellect and was a man of great energy and daring and determination. He was also a brilliant commander and shrewd diplomat.

Cleverly using the opportunities that came his way, Haidar Ali gradually rose in the Mysore army. He soon recognized the advantages of western military training and applied it to the troops under his own command.

In 1761, Haidar Ali overthrew Nanjaraj and established his authority over the Mysore state. He took over Mysore when it was weak and divided state and soon made it one of the leading Indian powers

Haidar Ali extended full control over the rebellious poligars (zamindars) and conquered the territories of Bidnur, Sunda, Sera, Canara, and Malabar.

Haidar Ali practiced religious toleration and his first Dewan and many other officials were Hindus.

Almost from the beginning of the establishment of his power, Haidar Ali was engaged in wars with the Maratha Sardars, the Nizam, and the British forces.

In 1769, Haidar Ali repeatedly defeated the British forces and reached the walls of Madras. He died in 1782 in the course of the second Anglo-Mysore War and was succeeded by his son Tipu.

Sultan Tipu, who ruled Mysore untill his death at the hands of the British in 1799, was a man of complex character. He was, for one an innovator.

Tipu Sultan’s desire to change with the times was symbolized in the Introduction of a new calendar, a new system of coinage, and new scales of weights and measures.

Tipu Sultan’s personal library contained books on such diverse subjects as religion, history, military science, medicine, and mathematics. He showed a keen interest in the French Revolution.

Tipu Sultan planted a 'Tree of Liberty' at Sringapatam and he became a member of a Jacobin club.

Tipu Sultan tried to do away with the custom of giving jagirs, and thus increased the state income. He also made an attempt to reduce the hereditary possessions of the poligars.

Tipu Sultan’s land revenue was as high as that of other contemporary rulers— it ranged up to 1/3rd of the gross produce. But he checked the collection of illegal ceases, and he was liberal in granting remissions.

Tipu Sultan’s infantry was armed with muskets and bayonets in fashion, which were, however, manufactured in Mysore.

Tipu Sultan made an effort to build a modern navy after 1796. For this purpose, two dockyards, the models of the ships being supplied.

Tipu Sultan was recklessly brave and, as a commander was, however, hasty in action and unstable in nature.

Tipu Sultan stood forth as a foe for the rising English power. The English, in turn, too as his most dangerous enemy in India.

Tipu Sultan gave money for the construction of goddess Sarda in the Shringeri Temple in 1791. He regularly gave gifts to as well to several other temples.

In 1799, while fighting the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, Tipu Sultan died.

Kerala

At the beginning of the 18th century, Kerala was divided into a large number of feudal chiefs and rajas.

The kingdom of Travancore rose into prominence after 1729 under King Martanda Varma, one of the leading statesmen of the 18th century.

Martanda Varma organized a strong army on the western model with the help of European officers and armed it with modern weapons. He also constructed a modern arsenal.

Martanda Varma used his new army to expand northwards and the boundaries of Travancore soon extended from Kanyakumari to Cochin.

Martanda Varma undertook many irrigation works, built roads and canals for communication, and gave active encouragement to foreign trade.

By 1763, all the petty principalities of Kerala had been absorbed or subordinated by the three big states of Cochin, Travancore, and Calicut.

Haidar Ali began his invasion of Kerala in 1766 and in the end annexed northern Kerala up to Cochin, including the territories of the Zamorin of Calicut.

Trivandrum, the capital of Travancore, became a famous center of Sanskrit scholarship during the second half of the 18th century.

Rama Varma, the successor of Martanda Varma, was himself a poet, a scholar, a musician, a renowned actor, and a man of great culture. He conversed fluently in English, took a keen interest in European affairs. He regularly used to read newspapers and journals published in London, Calcutta, and Madras.

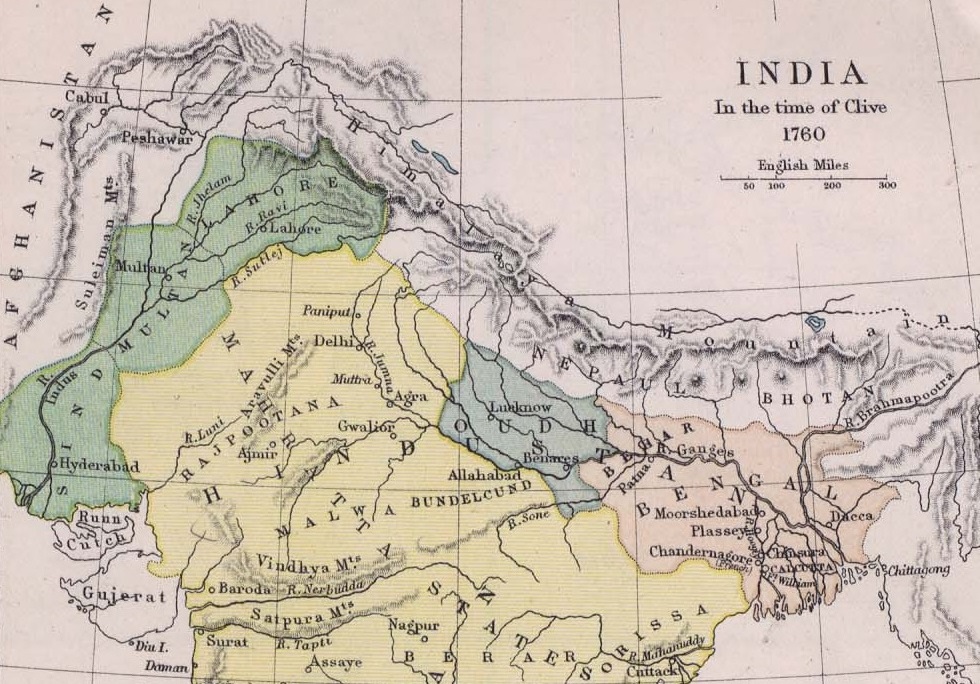

North Indian States in 18th Century

Following were the important North Indian States in 18th Century −

Avadh

The founder of the autonomous kingdom of Avadh was Saadat Khan Burhanul-Mulk who was appointed as Governor of Avadh in 1722. He was an extremely bold, energetic, iron-willed, and intelligent person.

At the time of Burhan-ul-Mulk’s appointment, rebellious zamindars had raised their heads everywhere in the province. They refused to pay the land tax, organized their own private armies, erected forts, and defied the Imperial Government.

For years, Burhan-ul-Mulk had to wage war upon them. He succeeded in suppressing lawlessness and disciplining the big zamindars and thus, increasing the financial resources of his government.

Burhan-ul-Mulk also carried out a fresh revenue settlement in 1723, as he was asked to improve the peasant condition by protecting them from oppression by the big zamindars.

Like the Bengal Nawabs, Burhan-ul-Mulk too did not discriminate between Hindus and 'Muslims. Many of his commanders and high officials were Hindus and he 'curbed refractory zamindars, chiefs, and nobles irrespective of their religion. His troops were well-paid, well-armed, and Well-trained.

Before his death in 1739, Burhan-ul-Mulk had become virtually independent and had made the province a hereditary possession.

Burhan-ul-Mulk was succeeded by his nephew Safdar Jang, who was simultaneously appointed the wazir of the Empire in 1748 and granted in addition the province of Allahabad.

Safdar Jang suppressed rebellious zamindars and made an alliance with the Maratha Sardars so that his dominion was saved from their incursions.

Safdar Jang gave a long period of peace to the people of Avadh and Allahabad before his death in 1754.

The Rajput States

Many Rajput states took advantage of the growing weakness of Mughal power to virtually free themselves from central control while at the same time increasing their influence in the rest of the Empire.

In the reigns of Farrukh Siyar and Muhammad Shah, the rulers of Amber and Marwar were appointed governors of important Mughal provinces such as Agra, Gujarat, and Malwa.

The internal politics of Agra, Gujarat, Malwa, etc. were often characterized by the same type of corruption, intrigue, and treachery as prevailed at the Mughal court.

Ajit Singh of Marwar was killed by his own son.

The most outstanding Rajput ruler of the 18th century was Raja Sawai Jai Singh of Amber (1681-1743).

Raja Sawai Jai Singh was a distinguished statesman, law-maker, and reformer. But most of all he shone as a man of science in an age when Indians were oblivious of scientific progress.

Raja Sawai Jai Singh founded the city of Jaipur in the territory taken from the Jats and made it a great seat of science and art.

Jaipur was built upon strictly scientific principles and according to a regular plan. Its broad streets are intersected at right angles.

Jai Singh was a great astronomer. He erected observatories with accurate and advanced instruments, some of his inventions can be still observed at Delhi, Jaipur, Ujjain, Varanasi, and Mathura. His astronomical observations were remarkably accurate.

Jai Singh drew up a set of tables, entitled Zij-i Muhammadshahi, to enable people to make astronomical observations. He had Euclid's "Elements of Geometry", translated into Sanskrit as also several works on trigonometry, and Napier's work on the construction and use of logarithms.

Jai Singh was also a social reformer. He tried to enforce a law to reduce the lavish expenditure which a Rajput had to incur on a daughter's wedding and which often led to infanticide.

This remarkable prince ruled Jaipur for nearly 44 years from 1699 to 1743.

The Jats

The Jats, a caste of agriculturists, lived in the region around Delhi, Agra, and Mathura.

Repression by Mughal officials drove the Jat peasants around Mathura to revolt. They revolted under the leadership of their Jat Zamindars in 1669 and then again in 1688.

Jats’ revolts were crushed, but the area remained disturbed. After the death of Aurangzeb, they created disturbances all around Delhi. Though originally a peasant uprising, the Jat revolt, led by zamindars, soon became predatory.

Jats plundered all and sundry, the rich and the poor, the jagirdars and the peasants, the Hindus and the Muslims.

The Jat state of Bharatpur was set up by Churaman and Badan Singh.

The Jat power reached its highest glory under Suraj Mal, who ruled from 1756 to 1763 and who was an extremely able administrator and soldier and a very wise statesman.

Suraj Mal extended his authority over a large area, which extended from the Ganga in the East to Chambal in the South, the Subah of Agra in the West to the Subah of Delhi in the North. His state included among others the districts of Agra, Mathura, Meerut, and Aligarh.

After the death of Suraj Mal in 1763, the Jat state declined and was split up among petty zamindars most of whom lived by plunder.

Bangash and Rohelas

Muhammad Khan Bangash, an Afghan adventure, established his control over the territory around Farrukhabad, between what are now Aligarh and Kanpur, during the reigns of Farrukh Siyar and Muhammad Shah.

Similarly, during the breakdown of administration following Nadir Shah's invasion, Ali Muhammad Khan carved out a separate principality, known as Rohilkhand, at the foothills of the Himalayas between the Ganga in the south and the Kumaon hills in the north with its capital first at Aolan in Bareilly and later at Rampur.

The Rohelas clashed constantly with Avadh, Delhi, and the Jats.

The Sikhs

Founded at the end of the 15th century by Guru Nanak, the Sikh religion spread among the Jat peasantry and other lower castes of Punjab.

The transformation of the Sikhs into a militant, fighting community was begun by Guru Hargobind (1606-1645).

It was, however, under the leadership of Guru Gobind Singh (1664-1708), the tenth and the last Guru of the Sikhs, that Sikhs became a political and military force.

From 1699 onwards, Guru Gobind Singh waged constant war against the armies of Aurangzeb and the hill rajas.

After Aurangzeb's death Guru Gobind Singh joined Bahadur Shah's camp as a noble of the rank of 5,000 Jat at and 5,000 sawar and accompanied him to the Deccan where he was treacherously murdered by one of his Pathan employees.

After Guru Gobind Singh's death, the institution of Guruship came to an end and the leadership of the Sikhs passed to his trusted disciple Banda Singh, who is more widely known as Banda Bahadur.

Banda rallied together the Sikh peasants of the Punjab and carried on a vigorous though unequal struggle against the Mughal army for eight years. He was captured in 1715 and put to death.

Banda Bahadur’s death gave a set-back to the territorial ambitions of the Sikhs and their power declined.

Punjab

At the end of the 18th century, Ranjit Singh, chief of the Sukerchakia Misl rose into prominence. A strong and courageous soldier, an efficient administrator, and a skillful diplomat, he was a born leader of men.

Ranjit Singh captured Lahore in 1799 and Amritsar in 1802. He soon brought all Sikh chiefs west of the Sutlej River under his control and established his own kingdom in the Punjab.

Ranjit Singh conquered Kashmir, Peshawar, and Multan. The old Sikh chiefs were transformed into big zamindars and jagirdars.

Ranjit Singh did not make any change in the system of lend revenue promulgated earlier by the Mughals. The amount of land revenue was calculated on the basis of 50 per cent of the gross produce.

Ranjit Singh built up a powerful, disciplined, and well-equipped army along European lines with the help of European instructors. His new army was not confined to the Sikhs. He also recruited Gurkhas, Biharis, Oriyas, Pathans, Dogras, and Punjabi Muslims.

Ranjit Singh set up the modern foundries to manufacture cannon at Lahore and employed Muslim gunners to man them. It is said that he possessed the second best army in Asia, the first was the army of the English East India Company

Bengal

Taking advantage of the growing weakness of the central authority, two men of exceptional ability, Murshid Quli Khan and Alivardi Khan, made Bengal virtually independent. Even though Murshid Quli Khan was made Governor of Bengal as late as 1717, he had been its effective ruler since 1700, when he was appointed its Dewan.

Murshid Quli Khan soon freed himself from central control though he sent regular tribute to the Emperor. He established peace by freeing Bengal of internal and external danger.

The only three major uprisings during Murshid Quli Khan’s rule were −

By Sitaram Ray,

By Udai Narayan, and

By Ghulam Muhammad.

Later Shujat Khan, and Najat Khan also rebelled during the Murshid Quli Khan’s reign.

Murshid Quli Khan died in 1727, and his son-in-law Shuja-ud-din ruled Bengal till 1739. In that year, Alivardi Khan deposed and killed Shuja-ud-din's son, Sarfaraz Khan, and made himself the Nawab.

Modern Indian History - Maratha Power

Rise and Fall of Martha Empire

The most important challenge to the decaying Mughal power came from the Maratha Kingdom, which was the most powerful of the Succession states. In fact, it alone possessed the strength to fill the political vacuum created by the disintegration of the Mughal Empire.

The Maratha Kingdom produced a number of brilliant commanders and statesmen needed for the task. But the Maratha Sardars lacked unity, and they lacked the outlook and program, which were necessary for founding an all-India empire.

Shahu, the grandson of Shivaji, had been a prisoner in the hands of Aurangzeb since 1689.

Aurangzeb had treated Shahu and his mother with great dignity, honor, and consideration, paying full attention to their religious, caste, and other needs, hoping perhaps to arrive at a political agreement with Shahu.

Shahu was released in 1707 after Aurangzeb's death.

A civil war broke out between Shahu at Satara and his aunt Tara Bai at Kolhapur who had carried out an anti-Mughal struggle since 1700 in the name of her son Shivaji II after the death of her husband Raja Ram.

Maratha Sardars, each one of whom had a large following of soldiers loyal to themselves alone began to side with one or the other contender for power.

Maratha Sardars used this opportunity to increase their power and influence by bargaining with the two contenders for power. Several of them even intrigued with the Mughal viceroys of the Deccan.

Balaji Vishwanath

Arising out of the conflict between Shahu and his rival at Kolhapur, a new system of Maratha government was evolved under the leadership of Balaji Vishwanath, the Peshwa of King Shahu.

The period of Peshwa domination in Maratha history was the most remarkable in which the Maratha state was transformed into an empire.

Balaji Vishwanath, a Brahmin, started life as a petty revenue official and then rose step by step as an official.

Balaji Vishwanath rendered Shahu loyal and useful service in suppressing his enemies. He excelled in diplomacy and won over many of the big Maratha Sardars.

In 1713, Shahu made him his Peshwa or the mulk pradhan (chief minister).

Balaji Vishwanath gradually consolidated Shabu's hold and his own over Maratha Sardars and over most of Maharashtra except for the region south of Kolhapur where Raja Ram's descendants ruled.

The Peshwa concentrated power in his office and eclipsed the other ministers and' seniors.

Balaji Vishwanath took full advantage of the internal conflicts of the Mughal officials to increase Maratha power.

Balaji Vishwanath had induced Zulfiqar Khan to pay the chauth and sardeshmukhi of the Deccan.

All the territories that had earlier formed Shivaji's kingdom were restored to Shahu who was also assigned the chauth and sardeshmukhi of the six provinces of the Deccan.

In 1719, Balaji Vishwanath, at the head of a Maratha force, accompanied Saiyid Hussain Ali Khan to Delhi and helped the Saiyid brothers in overthrowing Farrukh Siyar.

At Delhi, Balaji Vishwanath and the other Maratha Saradars witnessed at first hand the weakness of the Empire and were filled with the ambition of expansion in the North.

Balaji Vishwanath died in 1720 and his 20-year old son Baji Rao I succeeded as Peshwa. In spite of his youth, Baji Rao I was a bold and brilliant commander and an ambitious and clever statesman.

Baji Rao has been described as "the greatest exponent of guerrilla tactics after Shivaji".

Led by Baji Rao, the Marathas waged numerous campaigns against the Mughal Empire trying to compel the Mughal officials first to give them the right to collect the chauth of vast areas and then to cede these areas to the Maratha kingdom.

By 1740, when Baji Rao died, the Maratha had won control over Malwa, Gujarat, and parts of Bundelkhand. The Maratha families of Gaekwad, Holkar, Sindhia, and Bhonsle came into prominence during this period.

Baji Rao died in April 1740. In the short period of 20 years, he had changed the character of the Maratha state. From the kingdom of Maharashtra it had been transformed into an Empire expanding in the North (as shown in the map below).

Baji Rao's 18-year old son Balaji Baji Rao (also known as Nana Saheb) was the Peshwa from 1740 to 1761. He was as able as his father though less energetic.

King Shahu died in 1749 and by his will left all management of state affairs in the Peshwa's hands.

The office of the Peshwa had already become hereditary and the Peshwa was the de facto ruler of the state. Now Peshwa became the official head of the administration and, as a symbol of this fact, shifted the government to Poona, his headquarters.

Balaji Baji Rao followed in the footsteps of his father and further extended the Empire in different directions taking Maratha power to its height. Maratha armies now overran the whole of India.

Maratha control over Malwa, Gujarat, and Bundelkhand was consolidated.

Bengal was repeatedly invaded and, in 1751, the Nawab of Bengal had to cede Orissa.

In the South, the state of Mysore and other minor principalities were forced to pay tribute.

In 1760, the Nizam of Hyderabad was defeated at Udgir and was compelled to cede vast territories yielding an annual revenue of Rs. 62 lakhs.

Later, the arrival of Ahmad Shah Abdali and his alliance with the major kingdoms of North India (including an alliance with Najib-ud-daulah of Rohilkhand; Shuja-ud-daulah of Avadh, etc.) lead to third battle of Panipat (on January 14, 1761).

The Maratha army did not get any alliance and support resultantly was completely routed out in the third battle of Panipat.

The Peshwa's son, Vishwas Rao, Sadashiv Rao Bhau and numerous other Maratha commanders perished on the battle field as did nearly 28,000 soldiers. Those who fled were pursued by the Afghan cavalry and robbed and plundered by the Jats, Ahirs, and Gujars of the Panipat region.

The Peshwa, who was marching north to render help to his cousin, was stunned by the tragic news (i.e. defeat at Panipat). Already seriously ill, his end was hastened and he died in Jun 1761.

The Maratha defeat at Panipat was a disaster for them. They lost the cream of their army and their political prestige suffered a big blow.

Afghans did not get benefit from their victory. They could not even hold the Punjab. In fact, the Third Battle of Panipat did not decide who was to rule India, but rather who was not. The way was, therefore, cleared for the rise of the British power in India.

The 17-year old Madhav Rao became the Peshwa in 1761. He was a talented Soldier and statesman.

Within the short period of 11 years, Madhav Rao restored the lost fortunes of the Maratha Empire. He defeated the Nizam, compelled Haidar Ali of Mysore to pay tribute, and reasserted control over North India by defeating the Rohelas and subjugating the Rajput states and Jat chiefs.

In 1771, the Marathas brought back to Delhi Emperor Shah Alam who now became their pensioner.

Once again, however, a blow fell on the Marathas for Madhav Rao died of consumption in 1772.

The Maratha Empire was now in a state of confusion. At Poona there was a struggle for power between Reghunath Rao, the younger brother of Balaji Baji Rao, and Narayan Rao, the younger brother of Madhav Rao.

Narayan Rao was killed in 1773. He was succeeded by his posthumous son, Sawai Madhav Rao.

Out of frustration, Raghunath Rao approached to the British and tried to capture power with their help. This resulted in the First Anglo-Maratha War.

Sawai Madhav Rao died in 1795 and was succeeded by the utterly worthless Baji Rao II, son of Raghunath Rao.

The British had by now decided to put on end to the Maratha challenge to their supremacy in India.

The British divided the mutually-warring Maratha Sardars through clever diplomacy and then overpowered them in separate battles during the second Maratha War, 1803-1805, and the Third Maratha War, 1816-1819.

While other Maratha mates were permitted to remain as subsidiary states, the house of the Peshwas was extinguished.

Economic Conditions in 18th Century

India of the 18th century failed to make progress economically, socially, or culturally at a pace, which would have saved the country from collapse.

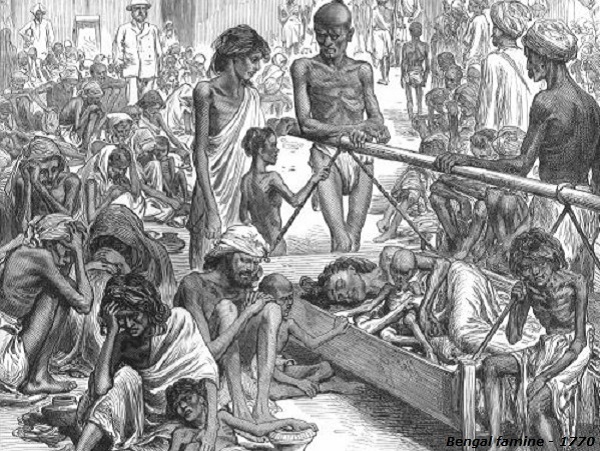

The increasing revenue demands of the state, the oppression of the officials, the greed and rapacity of the nobles, revenue-farmers, and zamindars, the marches and countermarches of the rival armies, and the depredations of the numerous adventurers roaming the land during the first half of the 18th century made the life of the people quite despicable.

India of those days, was also a land of contrasts. Extreme poverty existed side by side with extreme rich and luxury. On the one hand, there were the rich and powerful nobles steeped in luxury and comfort; on the other, backward, oppressed, and impoverished peasants living at the bare subsistence level and having to bear all sorts of injustices and inequities.

Even so, the life of the Indian masses was by and large better at this time than it was after over 100 years of British rule at the end of the 19th century.

Agriculture

Indian agriculture during the 18th century was technically backward and stagnant. The techniques of production had remained stationary for centuries.

The peasants tried to make up for technical backwardness by working very hard. They, In fact, performed miracles of production; moreover, they did not usually suffer from shortage of land. But, unfortunately, they seldom reaped the fruits of their labor.

Even though it was peasants’ produce that supported the rest of the society, their own reward was miserably inadequate.

Trade

Even though the Indian villages were largely self-sufficient and imported little from outside and the means of communication were backward, extensive trade within the country and between India and other countries of Asia and Europe was earned on under the Mughals.

India imported −

pearls, raw silk, wool, dates, dried fruits, and rose water from the Persian Gulf region;

coffee, gold, drugs, and honey from Arabia;

tea, sugar, porcelain, and silk from China;

gold, musk and woolen cloth from Tibet;

tin from Singapore;

spices, perfumes, attack, and sugar from the Indonesian islands;

ivory and drugs from Africa; and

woolen cloth, metals such as copper, iron, and lead, and paper from Europe.

India's most important article of export was cotton textiles, which were famous all over the world for their excellence and were in demand everywhere.

India also exported raw silk and silk fabrics, hardware, indigo, saltpeter, opium, rice, wheat, sugar, pepper and other spices, precious stones, and drugs.

Constant warfare and disruption of law and order, in many areas during the 18th century, banned the country's internal trade and disrupted its foreign trade to some extent and in some directions.

Many trading centers were looted by the Indians as well as by foreign invaders. Many of the trade routes were infested with organized bands of robbers, and traders and their caravans were regularly looted.

The road between the two imperial cities, Delhi and Agra, was made unsafe by the marauders. With the rise of autonomous provincial regimes and innumerable local chiefs, the number of custom houses or chowkies grew by leaps and bounds.

Every petty or large ruler tried to increase his income by imposing heavy customs duties on goods entering or passing though his territories.

The impoverishment of the nobles, who were the largest consumers of luxury products in which trade was conducted, also injured internal trade.

Many prosperous cities, centers of flourishing industry, were sacked and devastated.

Delhi was plundered by Nadir Shah;

Lahore, Delhi, and Mathura by Ahmad Shah Abdali;

Agra by the Jats;

Surat and other cities of Gujarat and the Deccan by Maratha chiefs;

Sarhind by the Sikhs, and so on.

The decline of internal and foreign trade also hit the industries hard in some parts of the country. Nevertheless, some industries in other parts of the country gained as a result of expansion in trade with Europe due to the activities of the European trading companies.

The important centers of textile industry were −

Dacca and Murshidabad in Bengal;

Patna in Bihar;

Surat, Ahmedabad, and Broach in Gujarat;

Chanderi in Madhya Pradesh

Burhanpur in Maharashtra;

Jaunpur, Varanasi, Lucknow, and Agra in U.P.;

Multan and Lahore in Punjab;

Masulipatam, Aurangabad, Chicacole, and Vishakhapatnam in Andhra;

Bangalore in Mysore; and

Coimbatore and Madurai in Madras.

Kashmir was a center of woolen manufactures.

Ship-building industry flourished in Maharashtra, Andhra, and Bengal.

Social Conditions in 18th Century

Social life and culture in the 18th century were marked by stagnation and dependence on the past.

There was, of course, no uniformity of culture and social patterns all over the country. Nor did all Hindus and all Muslims form two distinct societies.

People were divided by religion, region, tribe, language, and caste.

Moreover, the social life and culture of the upper classes, who formed a tiny minority of the total population, was in many respects different from the life and culture of the lower classes.

Hindu

Caste was the central feature of the social life of the Hindus.

Apart from the four vanes, Hindus were divided into numerous castes (Jatis), which differed in their nature from place to place.

The caste system rigidly divided people and permanently fixed their place in the social scale.

The higher castes, headed by the Brahmins, monopolized all social prestige and privileges.

Caste rules were extremely rigid. Inter-caste marriages were forbidden.

There were restrictions on inter-dining among members of different castes.

In some cases, persons belonging to higher castes would not take food touched by persons of the lower castes.

Castes often determined' the choice of ' profession, though exceptions did occur. Caste regulations were strictly enforced by caste councils and panchayats and caste chiefs through fines, penances (prayaschitya) and expulsion from the caste.

Caste was a major divisive force and element of disintegration in India of 18th century.

Muslim

Muslims were no less divided by considerations of caste, race, tribe, and status, even though their religion enjoined social equality.

The Shia and Sunni (two sects of Muslim religion) nobles were sometimes at loggerheads on account of their religious differences.

The Irani, Afghan, Turani, and Hindustani Muslim nobles, and officials often stood apart from each other.

A large number of Hindus converted to Islam carried their caste into the new religion and observed its distinctions, though not as rigidly as before.

Moreover, the sharif Muslims consisting of nobles, scholars, priests, and army officers, looked down upon the ajlaf Muslims or the lower class Muslims in a manner similar to that adopted by the higher caste Hindus towards the lower caste Hindus.

Modern Indian History - Status of Women

The family system in the 18th century India was primarily patriarchal, that is, the family was dominated by the senior male member, and inheritance was through the male line.

In Kerala, however, the family was matrilineal. Outside Kerala, women were subjected to nearly complete male control.

Women were expected to live as mothers and wives only, though in these roles they were shown a great deal of respect and honor.

Even during war and anarchy, women were seldom molested and were treated with respect.

A European traveler, Abbe J.A. Dubois, commented, at the beginning of the 19th century −

"A Hindu woman can go anywhere alone, even in the most crowded places, and she need never fear the impertinent looks and jokes of idle loungers....A house inhabited solely by women is a sanctuary which the most shameless libertine would not dream of violating."

The women of the time possessed title individuality of their own. This does not mean that there were no exceptions to this rule. Ahilya Bai administered Indore with great success from 1766 to 1796.

Many Hindu and Muslim ladies played important roles in 18th century politics.

While women of the upper classes were not supposed to work outside their homes, peasant women usually worked in the fields and women of the poorer classes often worked outside their homes to supplement the family income.

The purdah was common mostly among the higher classes in the North. It was not practiced in the South.

Boys and girls were not permitted to mix with each other.

All marriages were arranged by the heads of the families. Men were permitted to have more than one wife, but except for the well-off, they normally had only one.

On the other hand, a woman was expected to marry only once in her life-time.

The custom of early marriage prevailed all over the country.

Sometimes children were married when they were only three or four years of age.

Among the upper classes, the evil customs of incurring heavy expenses on marriages and of giving dowry to the bride prevailed.

The evil of dowry was especially widespread in Bengal and Rajputana culture.

In Maharashtra, it was curbed to some extent by the energetic steps taken by the Peshwas.

Two great social evils of the 18th century India, apart from the caste system, were the custom of sati and the harrowing condition of widows.

Sati involved the rite of a Hindu widow burning herself (self-immolation) along with the body of her dead husband.

Sati practice was mostly prevalent in Rajputana, Bengal, and other parts of northern India. In the South it was uncommon: and the Marathas did not encourage it.

Even in Rajputana and Bengal, it was practiced only by the families of rajas, chiefs, big zamindars, and upper castes.

Widows belonging to the higher classes and higher castes could not remarry, though in some regions and in some castes, for example, among non-Brahmins in Maharashtra, the Jats and people of the hill-regions of the North, widow remarriage was quite common.

There were all sorts of restrictions on her clothing, diet, movements, etc. In general, she was expected to renounce all the pleasures of the earth and to serve selflessly the members of her husband's or her brother's family, depending on where she spent the remaining years of her life.

Raja Sawai Jai Singh of Amber and the Maratha General Prashuram Bhau tried to promote widow remarriage but failed.

Modern Indian History - Arts and Paintings

Culturally, India showed signs of exhaustion during the 18th century. But at the same time, culture remained wholly traditionalist as well as some development took place.

Many of the painters of the Mughal School migrated to provincial courts and flourished at Hyderabad, Lucknow, Kashmir, and Patna.

The paintings of Kangra and Rajput Schools revealed new vitality and taste.

In the field of architecture, the Imambara of Lucknow reveals proficiency in technique.

The city of Jaipur and its buildings are an example of continuing vigor.

Music continued to develop and flourish in the 18th century. Significant progress was made in this field in the reign of Mohammad Shah.

Literary Works

Poetry in reality, all the Indian languages lost its touch with life and became decorative, artificial, mechanical, and traditional.

A noteworthy feature of the literary life of the 18th century was the spread of Urdu language and the vigorous growth of Urdu poetry.

Urdu gradually became the medium of social intercourse among the upper classes of northern India.

The 18th century Kerala also witnessed the full development of Kathakali literature, drama, and dance.

Tayaumanavar (1706-44) was one of the best exponents of sittar poetry in Tamil. In line with other poets, he protested against the abuses of temple-rule and the caste system.

In Assam, literature developed under the patronage of the Ahom kings.

Heer Ranjha, the famous romantic epic in Punjabi, was composed at this time by Warris Shah.

For Sindhi literature, the 18th century was a period of enormous achievement.

Shah Abdul Latif composed his famous collection of poems.

Modern Indian History - Social Life

Cultural activities of the time were mostly financed by the Royal Court, rulers, and nobles and chiefs whose impoverishment led to their gradual neglect.

Friendly relations between Hindus and Muslims were a very healthy feature of life in 18th century.

Politics were secular in spite of having fights and wars among the chiefs of the two groups (Hindus and Muslims).

There was little communal bitterness or religious intolerance in the country.

The common people in the villages and towns who fully shared one another’s joys and sorrows, irrespective of religious affiliations.

Hindu writers often wrote in Persian while Muslim writers wrote in Hindi, Bengali, and other vernaculars.

The development of Urdu language and literature provided a new meeting ground between Hindus and Muslims.

Even in the religious sphere, the mutual influence, and respect that had been developing in the last few centuries as result of the spread of the Bhakti movement among Hindus and Sufism among Muslim saints was the great example of unity.

Education

Education was not completely neglected in 18th century India, but it was on the whole defective.

It was traditional and out of touch with the rapid developments in the West. The knowledge which it imparted was confined to literature, law, religion, philosophy, and logic, and excluded the study of physical and natural sciences, technology, and geography.

In all fields original thought was discouraged and reliance placed on the ancient learning.

The centers of higher education were spread all over the country and were usually financed by nawabs, rajas, and rich zamindars.

Among the Hindus, higher education was based on Sanskrit learning and was mostly confined to Brahmins.

Persian education being based on the official language of the time was equally popular among Hindus and Muslims.

A very pleasant aspect of education then was that the teachers enjoyed high prestige in the community. However, a bad feature of it was that girls were seldom given education, though some women of the higher classes were an exception.

The Beginnings of European Trade

India's trade relations with Europe go back to the ancient days of the Greeks. During the middle Ages, trade between Europe and India and South-East Asia was carried through various routes.

Trade Routes

Major trade routes were −

Through sea - along the Persian Gulf;

Through land- through Iraq and Turkey, and then again by sea to Venice and Genoa;

Third was via the Red Sea and then overland to Alexandria in Egypt and from there again by sea to Venice and Genoa.

The fourth one was less used i.e. overland route through the passes of the North-West frontier of India, across Central Asia, and Russia to the Baltic.

The Asian part of the trade was carried on mostly by Arab merchants and sailors, while the Mediterranean and European part was the virtual monopoly of the Italians.

Goods from Asia to Europe passed through many states and many hands. Every state levied tolls and duties while every merchant made a substantial profit.

There were many other obstacles, such as pirates and natural calamities on the way. Yet the trade remained highly profitable. This was mostly due to the pressing demand of the European people for Eastern spices.

The Europeans needed spices because they lived on salted and peppered meat during the winter months, when there was little grass to feed the cattle, and only a liberal use of spices could make this meat palatable. Consequently, European food was as highly spiced as Indian food till the 17th century.

The old trading routes between the East and the West came under Turkish control after the Ottoman conquest of Asia Minor and the capture of Constantinople in 1453.

The merchants of Venice and Genoa monopolized the trade between Europe and Asia and refused to let the new nation states of Western Europe, particularly Spain, and Portugal, have any share in the trade through these old routes.

The trade with India and Indonesia was highly prized by the West Europeans to be so easily given up.

The demand for spices was pressing and the profits to be made in their trade inviting.

The reputedly fabulous wealth of India was an additional attraction as there was an acute shortage of gold all over Europe, and gold was essential as a medium of exchange if the trade was to grow unhampered.

The West European states and merchants therefore began to search for new and safer sea routes to India and the Spice Islands of Indonesia, (at that time popular as the East Indies).

The West Europeans wanted to break the Arab and Venetian trade monopolies, to bypass Turkish hostility, and to open direct trade relations with the East.

The West European were well-equipped to do so as great advances in shipbuilding and the science of navigation had taken place during the 15th century. Moreover, the Renaissance had generated a great spirit of adventure among the people of Western Europe.

The first steps were taken by Portugal and Spain whose seamen, sponsored and controlled by their governments, began a great era of geographical discoveries.

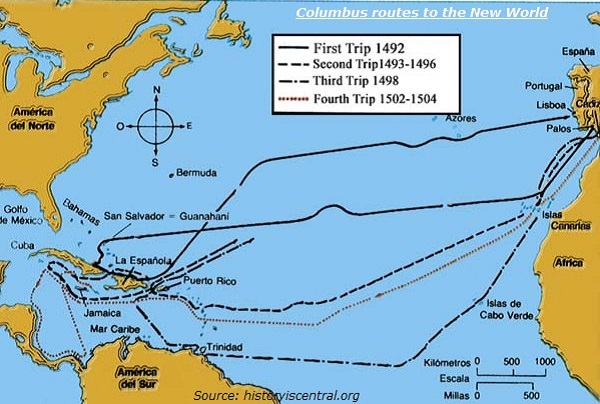

In 1494, Columbus of Spain set out to reach India and discovered America instead of India.

Modern Indian History - The Portuguese

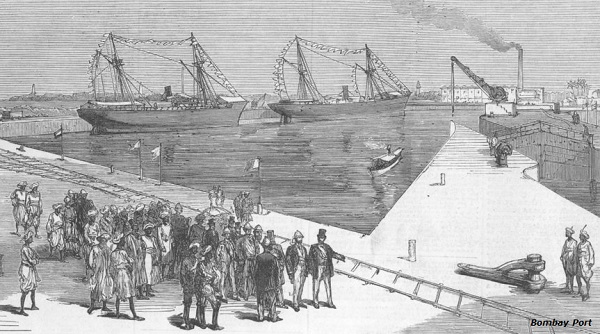

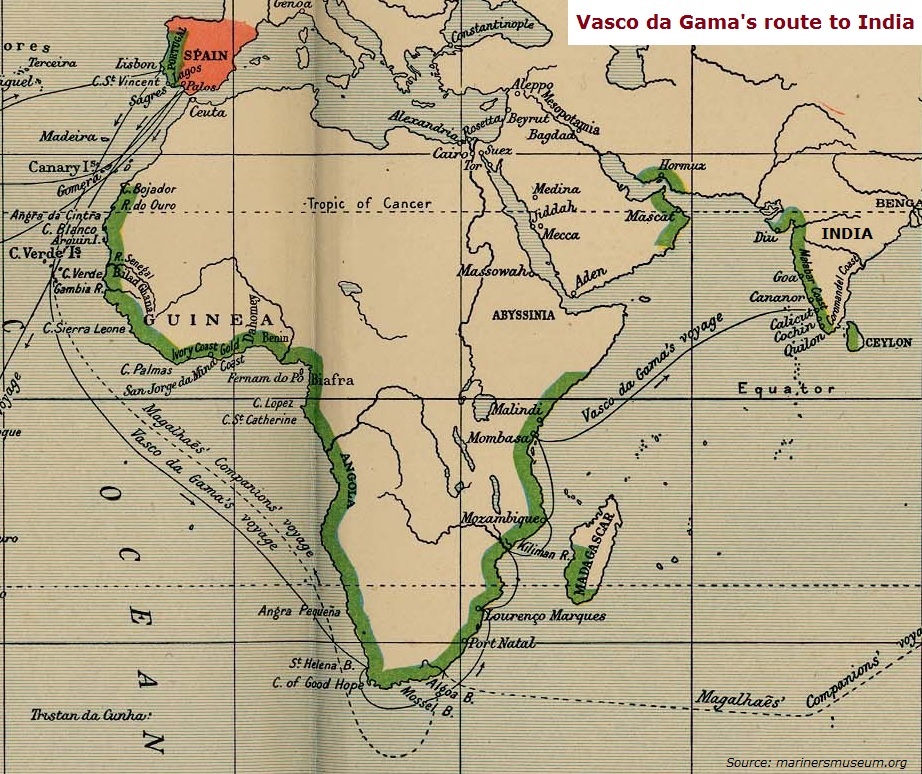

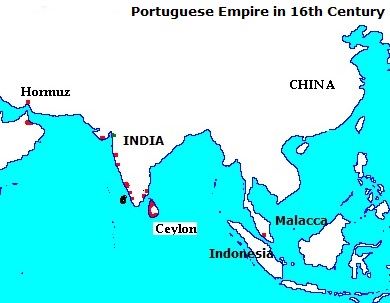

In 1498, Vasco da Gama of Portugal discovered a new and all-sea route from Europe to India. He sailed around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) and reached Calicut (as shown in the map given below).

Vasco da Gama returned with a cargo, which sold for 60 times the cost of his voyage.

Columbus and Vasco da Gama’s sea routes along with other navigational discoveries opened a new chapter in the history of the world.

Adam Smith wrote later that the discovery of America and the Cape route to India were "the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind."

The new continent was rich in precious metals. Its gold and silver poured into Europe where they powerfully stimulated trade and provided some of the capital, which was soon to make European nations the most advanced in trade, industry, and science.

America became a new and inexhaustible market for European manufacturers.

Some other source of early capital accumulation or enrichment for European countries was their penetration into African land in the middle of the 15th century.

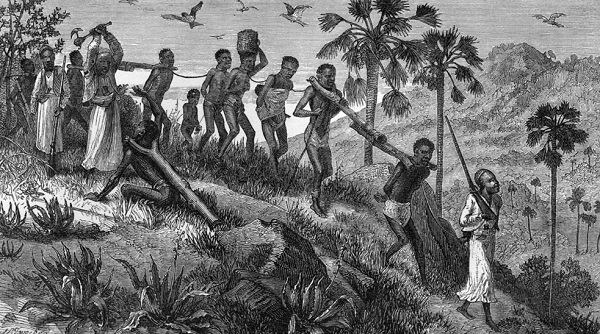

In the beginning, gold and ivory of Africa had attracted the foreigner. Very soon, however, trade with Africa concentrated on the slave trade.

In the 16th century, this trade was a monopoly of Spain and Portugal; later it was dominated by Dutch, French, and British merchants.

Year after year (particularly after 1650), thousands of Africans were sold as slaves in the West Indies and in North and South America.

The slave ships carried manufactured goods from Europe to Africa, exchanged them on the coast of Africa for Negroes, took these slaves across the Atlantic and exchanged them for the colonial produce of plantations or mines, and finally brought back and sold this produce in Europe.

While no exact record of the number of Africans sold into slavery exists, historians' estimate, ranged between 15 and 50 million.

Slavery was later abolished in the 19th century after it had ceased to play an important economic role, but it was openly defended and praised as long as it was profitable.

Monarchs, ministers, members of Parliament, dignitaries of the church, leaders of public opinion, and merchants and industrialists supported the slave trade.

On the other hand, in Britain, Queen Elizabeth, George III, Edmund Burke, Nelson, Gladstone, Disraeli, and Carlyle were some of the defenders and apologists of slavery.

Portugal had a monopoly of the highly profitable Eastern trade for nearly a century. In India, Portugal established her trading settlements at Cochin, Goa, Diu, and Daman.

From the beginning, the Portuguese combined the use of force with trade and they were helped by the superiority of their armed ships which enabled them to dominate the seas.

Portuguese also saw that they could take advantage of the mutual rivalries of the Indian princes to strengthen their position.

Portuguese intervened in the conflict between the rulers of Calicut and Cochin to establish their trading centers and forts on the Malabar Coast. Likewise, they attacked and destroyed Arab shipping, brutally killing hundreds of Arab merchants and seamen. By threatening Mughal shipping, they also succeeded in securing many trading concessions from the Mughal Emperors.

Under the viceroyalty of Alfanso d’ Albuquerque, who captured Goa in 1510, the Portuguese established their domination over the entire Asian land from Hormuz in the Persian Gulf to Malacca in Malaya and the Spice Islands in Indonesia.

Portuguese seized Indian territories on the coast and waged constant war to expand their trade and dominions and safeguard their trade monopoly from their European rivals.

In the words of James Mill (the famous British historian of the 19th century): "The Portuguese followed their merchandise as their chief occupation, but like the English and the Dutch of the same period, had no objection to plunder, when it fell in their way."

The Portuguese were intolerant and fanatical in religious matters. They indulged in forcible conversion offering people the alternative of Christianity or sword.

Portuguese approach was particularly hateful to people of India (where the religious tolerance was the rule). They also indulged in inhuman cruelties and lawlessness.

In spite of their barbaric behavior, Portuguese possessions in India survived for a century because −

They (Portuguese) enjoyed control over the high seas;

Their soldiers and administrators maintained strict discipline; and

They did not have to face the fight of the Mughal Empire as South India was outside Mughal influence.

Portuguese clashed with the Mughal power in Bengal in 1631 and were driven out of their settlement at Hugli.

The Portuguese and the Spanish had left the English and the Dutch far behind during the 15th century and the first half of the 16th century. But, in the latter half of the 16th century, England and Holland, and later France, all growing commercial and naval, powers, waged a fierce struggle against the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly of world trade.

Portuguese hold over the Arabian Sea had been weakened by the English and their influence in Gujarat had become negligible.

Decline of Portuguese

Portugal was, however, incapable of maintaining for long its trade monopoly or its dominion in the East because of −

Its population was less than a million;

Its Court was autocratic and decadent;

Its merchants enjoyed much less power and prestige than its landed aristocrats;

It lagged behind in the development of shipping, and

It followed a polity of religious intolerance.

It became a Spanish dependency in 1530.

In 1588, the English defeated the Spanish fleet called the Armada and shattered Spanish naval supremacy forever.

Modern Indian History - The Dutch

The weakening of Portuguese enabled the English and the Dutch merchants to use the Cape of Good Hope route to India and so to join in the race for empire in the East.

At the end, the Dutch gained control over Indonesia and the British over India, Ceylon, and Malaya.

In 1595, four Dutch ships sailed to India via the Cape of Good Hope.

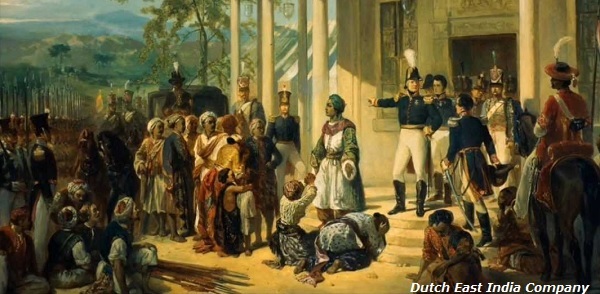

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company was formed and the Dutch States General (the Dutch parliament) gave it a Charter empowering it to make war, conclude treaties, acquire territories, and build fortresses.

The main interest of Dutch was not in India, but in the Indonesian Islands of Java, Sumatra, and the Spice Islands where spices were produced.

Dutch forced back the Portuguese from the Malay Straits and the Indonesian Islands and, in 1623, defeated English who attempted to establish themselves on the islands.

In the first half of 17th century, Dutch had successfully seized the most important profitable part of Asian trade.

Dutch also established trading depots at −

Surat, Broach, Cambay, and Ahmadabad in Gujarat;

Cochin in Kerala;

Nagapatam in Madras;

Masulipatam in Andhra

Chinsura in Bengal;

Patna in Bihar; and

Agra in Uttar Pradesh.

In 1658, also conquered Ceylon from the Portuguese.

Dutch exported indigo, raw silk, cotton textiles, saltpeter, and opium from India.

Like the Portuguese, Dutch treated the people of India with cruelty and exploited them ruthlessly.

Modern Indian History - The English

An English association or company to trade with the East was formed in 1599 under the auspices of a group of merchants known as the Merchant Adventurers. The company was granted a Royal Charter and the exclusive privilege to trade in the East by Queen Elizabeth on 31 December 1600. The company was named as the East India Company.

From the beginning, it was linked with the monarchy: Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) was one of the shareholders of the company.

The first voyage of the English East India Company was made in 1601 when its ships sailed to the Spice Islands of Indonesia.

In 1608, a factory was established at Surat, on the West coast of India and sent Captain Hawkins to Jahangir’s Court to obtain Royal favors.

Initially, Hawkins was received in a friendly manner. He was given a mansab and a jagir. Later, he was expelled from Agra as a result of Portuguese intrigue. This convinced the English (need) to overcome Portuguese influence at the Mughal Court if they were to obtain any concessions from the Imperial Government.

English defeated a Portuguese naval squadron at Swally near Surat in 1612 and then again in 1614. These victories led the Mughals to hope that in view of their naval weakness, they could use the English to counter the Portuguese on the sea.

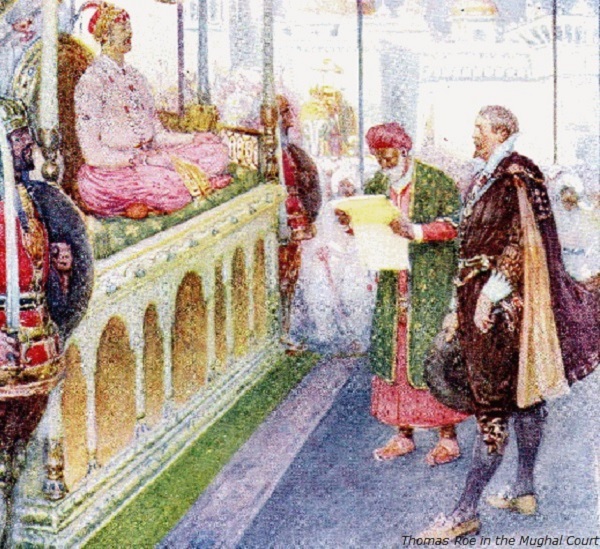

In 1615, English ambassador Sir Thomas Roe reached the Mughal Court (shown in the image given above) and exerted pressure on the Mughal authorities by taking advantage of India's naval weakness. English merchants also harassed the Indian traders while shipping through the Red Sea and to Mecca. Thus, combining entreaties with threats, Roe succeeded in getting an imperial Farman to trade and establish factories in all parts of the Mughal Empire.

Roe's success further angered the Portuguese and a fierce naval battle between the two countries began in 1620 that ended with English victory.

Hostilities between the English and Portuguese came to an end in 1630.

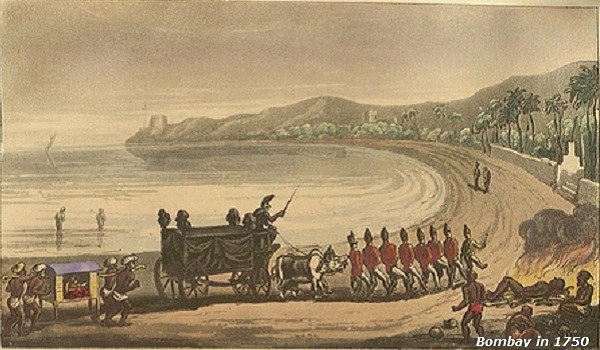

In 1662, the Portuguese gave the Island of Bombay to King Charles II of England as dowry for marrying with a Portuguese Princess.

Eventually, the Portuguese lost all their possessions in India except Goa, Diu, and Daman.

The English Company fell out with the Dutch Company over division of the spice trade of the Indonesian Islands. Finally, the Dutch nearly expelled the English from the trade of the Spice Islands and the later were compelled to concentrate on India where the situation was more favorable to them.

The intermittent war in India between the English and the Dutch had begun in 1654 and ended in 1667; when the English gave up all claims to Indonesia while the Dutch agreed to leave alone the English settlements in India.

The English, however, continued their efforts to drive out the Dutch from the Indian trade and by 1795, they had expelled the Dutch from their last possession in India.

The English East India Company had very humble beginnings in India. Surat was the center of its trade till 1687.

Throughout the trading period, the English refrained petitioners before the Mughal authorities. By 1623, they had established factories at Surat, Broach, Ahmedabad, Agra, and Masulipatam.

East India Company (1600-1744)

The English East Company had very humble beginnings in India. Surat was the center of its trade till 1687.

The Beginning and Growth of East India Company

By 1623, English East India Company had established factories at Surat, Broach, Ahmedabad, Agra, and Masulipatam.

From the very beginning, the English trading company tried to combine trade and diplomacy with war and control of the territory where their factories were situated.

In 1625, the East India Company's authorities at Surat made an attempt to fortify their factory, but the chiefs of the English factory were immediately imprisoned and put in irons by the local authorities of the Mughal Empire.

The Company's English rivals made piratical attacks on Mughal shipping, the Mughal authorities imprisoned the President of the Company in retaliation at Surat and members of his Council and released them only on payment of £18,000.

Conditions in the South India were more favorable to the English, as they did not have to face a strong Indian Government there.

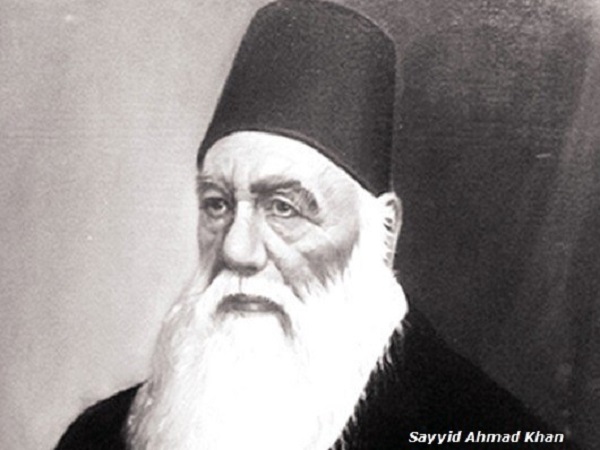

The English opened their first factory in the South at Masulipatam in 1611. But they soon shifted the center of their activity to Madras the lease of which was granted to them by the local king in 1639.